Inspired by the energy bottled up in George Lucas’ American Graffiti and playing off the rambunctious stage set by Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High, the ‘80s teen movie scene is one of the rare categories that gets talked about like an actual genre in its own right. Led by major players such as John Hughes, Cameron Crowe, Joel Schumacher, and Howard Deutch, among others, these films collected some of the brightest acting talents of the time and gave their young characters a voice.

This wasn’t the first time youth in film were given agency — you can see scarce examples in the ‘50s with Blackboard Jungle and Rebel Without a Cause — but it was the first time the teen genre had some delineation. You had sophomoric sex comedies like Porky’s and Screwballs but you also had highly insightful dramedies that allowed younger audiences to find catharsis while still retaining some of the sophomoric attitudes of adolescence. We’re talking movies like The Breakfast Club, St. Elmo’s Fire, and Pretty in Pink, where art was now imitating life instead of the other way around. And one thing was for sure: teen movies could no longer be written off as drive-in fodder.

Actor Andrew McCarthy is one of the handful of stars that gets mentioned when discussing the Brat Pack, an unofficial name for the ensemble of talents across the myriad teen flicks of the time. This also includes Molly Ringwald, Rob Lowe, Demi Moore, Robert Downey Jr., Anthony Michael Hall, Emilio Estevez, Ally Sheedy, and Judd Nelson, with some argument given for others. In his documentary, Brats, McCarthy explores the weight that came with the Brat Pack name and attempts to face the demons that he, and maybe others, have been living with because of it.

Serving as director, McCarthy attempts to track down and interview most of the members of the Brat Pack, along with some adjacent members (Anthony Michael Hall, however, is strangely omitted from most discussion). He doesn’t, however, have success with Ringwald and Nelson who he implies wanted to be left out of the conversation.

Today, the term “Brat Pack” is emblematic of our nostalgia for a time in history when teen movies were on top of the world and evolving at a rate we’d never really seen before — revered films that would positively affect the lives of many and collectively help change the standards for depth of characters in future cinema. However, if you were a “member” of the Brat Pack, this term meant something completely different.

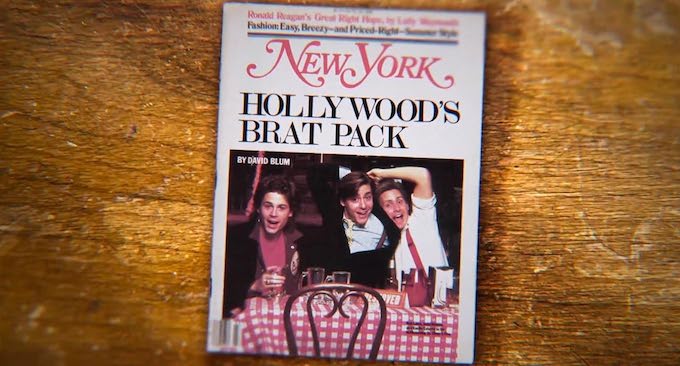

Coined by writer David Blum in a 1985 cover story for New York magazine, “Brat Pack” had a major impact on the likes of McCarthy and others who saw it as a mark of (career) death. Some of these stars were trained actors who had the same aspirations that a young James Dean and Marlon Brando once had. However, they felt personally offended by the moniker and inadvertently stifled by it. When interviewed by McCarthy, Estevez explains that he passed up on some projects he felt tried to capitalize on the movement, and encouraged his Brat Pack brethren to do the same.

It would seem to be — and as Blum suggests — that these stars were the future of Hollywood. This was no Annette and Frankie; these performers were quite good. However, typecasting and the natural lifespan of youth may have played a part in the lack of success after the ‘80s. Some made it out fairly well: Lowe and Moore endured popularity in the coming decades but others like Sheedy and Nelson never had the momentum they may have hoped for. Even Ringwald, the de facto face of the Brat Pack, seemed to be affected by being a member. But was it the label itself that was to blame?

If you were to ask McCarthy, it certainly was. Although, I’m not so sure I buy into this assessment. With any unprecedented level of success or fame, you get something called “Imposter Syndrome,” which is like a voice in the back of your head telling you that you’re really just tricking everyone into thinking that you’re talented. And when somebody writes a public piece seeming to write off you and your cohorts as “brats,” those with a certain insecurity and lack of resolve may let this affect them negatively. But even Estevez postulates that “we have no control over how we’re remembered.”

Despite drawing out this therapy session far too long here, you have to credit McCarthy who approaches the infamous Blum himself in a marvelous sit-down that becomes crucial to the film. Low-stakes documentaries typically lack this kind of tension which becomes earned in this scene between the two men, who each stands his own ground. McCarthy asks the writer if he regrets anything he wrote but Blum reminds McCarthy that all press is good press, and that you have to be willing to endure criticism if you want the fame.

For outsiders, “Brat Pack” was and is a glorious badge of honor. In their own interviews, Lea Thompson and Jon Cryer both remind viewers that they weren’t ever considered members of the ostensibly exclusive club. However, Thompson says she always kinda wished she had been. But would it have negatively affected either of their careers? Thompson and Cryer both landed successful sitcoms at one point, years later. But would this not have happened if they were Brat Pack members? Aside from their respective shows, their filmography trends similarly to McCarthy’s, Lowe’s, and even Ringwald’s. There’s no real correlation here. Typecasting is a strong force but has more to do with how the public and creators see you than it does with a single writer’s label of you from a magazine article.

If anything, Brats provides food for thought on the transitory nature of success and how a celebrity’s role within the zeitgeist affects the celebrity themselves. More than a way to rouse the audience against the eponymous label, the documentary merely serves as a character study of a struggling artist trying to find catharsis for his own failures. Eager to point the blame at the writer who coined the term rather than at his own pliability, McCarthy still allows us, intentionally or not, to watch his exploration unfold from an objective position. We don’t feel like we’re being emotionally manipulated by his very personal story, and we even begin to question his own role in his career’s fate.

Twizard Rating: 80

*Originally published at Popzara.com

Leave a comment