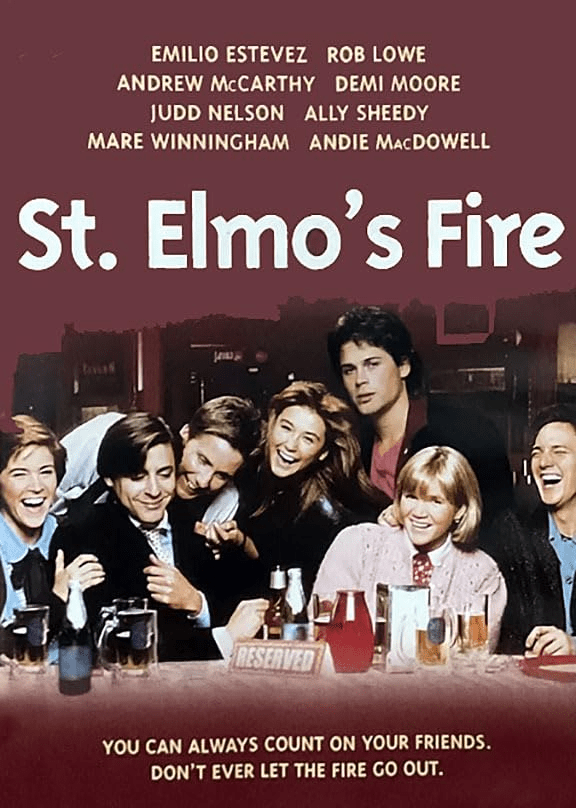

I’m not so sure it was the term “Brat Pack” that ostensibly tarnished the careers of Emilio Estevez, Judd Nelson, and Andrew McCarthy; more likely it was St. Elmo’s Fire.

It’s no coincidence that Rob Lowe and Demi Moore, when interviewed by McCarthy in his recent documentary Brats, didn’t quite share in the filmmaker’s position that the “Brat Pack” stigma was harmful. While both actors have enjoyed lengthy careers, both Lowe and Moore’s characters get served fairly well by Joel Schumacher’s 1985 zeitgeist drama. However, they’re really the only ones.

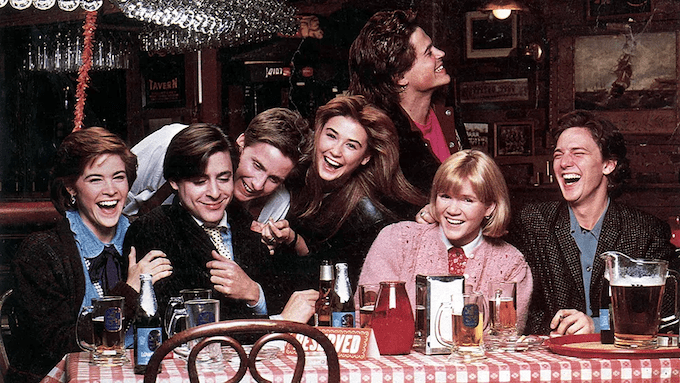

St. Elmo’s Fire is about seven college friends who just graduated from Georgetown University. A few of them have already started on their careers while others are still figuring it out. Estevez plays a law student who drops out to pursue his career as a stalker; Nelson realizes he wants to be in politics but it doesn’t matter which side he’s on, as long as it pays well; Ally Sheedy plays his longtime girlfriend who hopes that he can stop sleeping around enough for them to settle down; McCarthy is an obituary writer with dreams of pontificating about his myopic views on love and marriage for the whole world to read.

On the other hand, Moore’s Jules and Lowe’s Billy are two sides of the same disillusioned coin. Jules has no relationship with her parents but was raised around sophistication to the point that she now can’t ditch her expensive lifestyle. Constantly requesting advances on her paycheck, she gets fired from her job and takes up a cocaine addiction.

Meanwhile, Billy is that guy who was insanely popular in school but never had any career aspirations. He’s in a band but somehow a career in the arts never enters the conversation, perhaps because he was told by somebody that he must have a “normal” job. Well, he’s been fired “20 times since graduation.” In a way, both he and Jules are still holding onto the security of college: the security of professors, the security of friends, and the security of a family who is willing to let you screw around as long as you finish with a degree.

St. Elmo’s Fire touches on the pressures of following in the direction paved for you by your major. We often feel obligated to pursue a career that matches our degree but what if life has something else in store? Will we disappoint the people who helped get us through school? Sadly, the movie doesn’t delve into this notion far enough — but that’s honestly a good thing because I’m not so sure the writers could’ve appropriately handled such a theme.

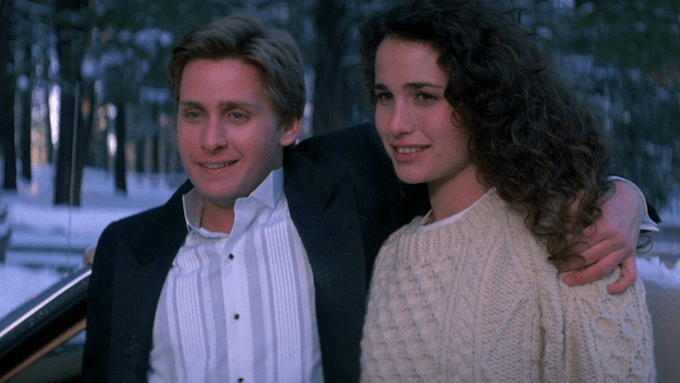

Co-written by Schumacher and Carl Kurlander, St. Elmo’s Fire suffers when it becomes too exploratory into its characters’ lives. This is why we walk away from it remembering Moore and Lowe. While we’re busy looking subjectively at the goings-on of Estevez, Nelson, Sheedy, and McCarthy, we’re given only what we need from Jules and Billy. We see them almost exclusively when they’re interacting with the other characters (with a few exceptions, of course). We barely see where they work, where they live (although Jules’ pink apartment is the best set in the movie), or how they get from one place to another. It’s almost always objective. At the very least, the movie prioritizes its other characters when it comes to the plot. For instance, when Estevez is stalking Andie MacDowell, we’re immersed in this scenario. And when McCarthy and Sheedy are expounding about life and love, we know what’s inside their heads all too well. For Moore and Lowe, we’re required to read into their situations a bit more, thus engaging us with the movie on a new level.

On a different note, the film offers an intriguing look at this group of friends who’ve seen each other every day for the past four years of their lives but now must transition into the real world. It’s not practical to be with your friends every day, nor is it healthy. Luckily, this gets realized by the end of the movie but we have to go through hell to get there — hell and a superfluous Emilio Estevez sub-plot.

Estevez’s character and storyline could’ve been scrapped from the film entirely and it wouldn’t have really changed anything in terms of the plot or the rest of the characters. Not only is his behavior outright sickening for anyone in the audience but it exposes the writers’ biggest flaw: They don’t have a rational view of obsession. They think that when someone is obsessed, they say everything that’s on their minds, they have no control over their inhibitions, they change their entire jobs, and they camp outside of their crush’s jobs, parties, and winter cabins.

And by virtue of not seeing anything wrong with this behavior, one also wouldn’t think that your other characters would see anything wrong with it either. If Estevez’s insanity isn’t bad enough, MacDowell’s response to his insanity is even more preposterous. Upon discovering that Estevez has stalked her on her vacation in the mountains, MacDowell invites him inside to meet her boyfriend, fixes his car, and then takes a nice Polaroid picture of them together for posterity (????).

Simply put, there’s a wide distance between how the writers view realistic behavior and how people actually behave. We see this in smaller doses elsewhere with repartee that sounds like it was written by Kevin Smith but with less logic behind his opinions. Set in a world where every person is unbelievably well-scripted, these characters always have the wittiest responses to what their friends say; nobody talks like this!

As frustrating as the script and its characters can be much of the time, Schumacher actually does a decent job creating a cohesive atmosphere and affable environment of which these spoiled characters inhabit — bolstered even more by David Foster’s period-friendly music.

Still relating to its audience on some level, St. Elmo’s Fire will surely connect with anyone who’s experienced the strange meandering that follows your entire life’s worth of schooling up to that point. However, later films like Reality Bites and Singles do a much better job of assessing and navigating the treacherous waters of early adulthood.

These types of post-grad malaise movies featuring ensemble casts are always a tricky tightrope act, requiring us to be invested in multiple characters who each have some balance between likability and imperfection. Unfortunately, almost everyone in St. Elmo’s Fire is unlikable to a degree. And even when they’re not, they enable their friends to continue in their unlikable ways. Brats, indeed.

Twizard Rating: 71

I’m a one-man team, so every time you purchase something through one of my affiliate links, I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you!

Leave a comment