American Graffiti inspired a whole lot of movies about life, love, and nascent stages of the American Dream. Riding alongside George Lucas’ seminal 1973 movie is Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde. Tangential to American Graffiti with some of its themes, the ’67 masterpiece not only helped change American cinema forever with its honesty and grit but perhaps misguided promising young filmmakers about what New Hollywood looked like.

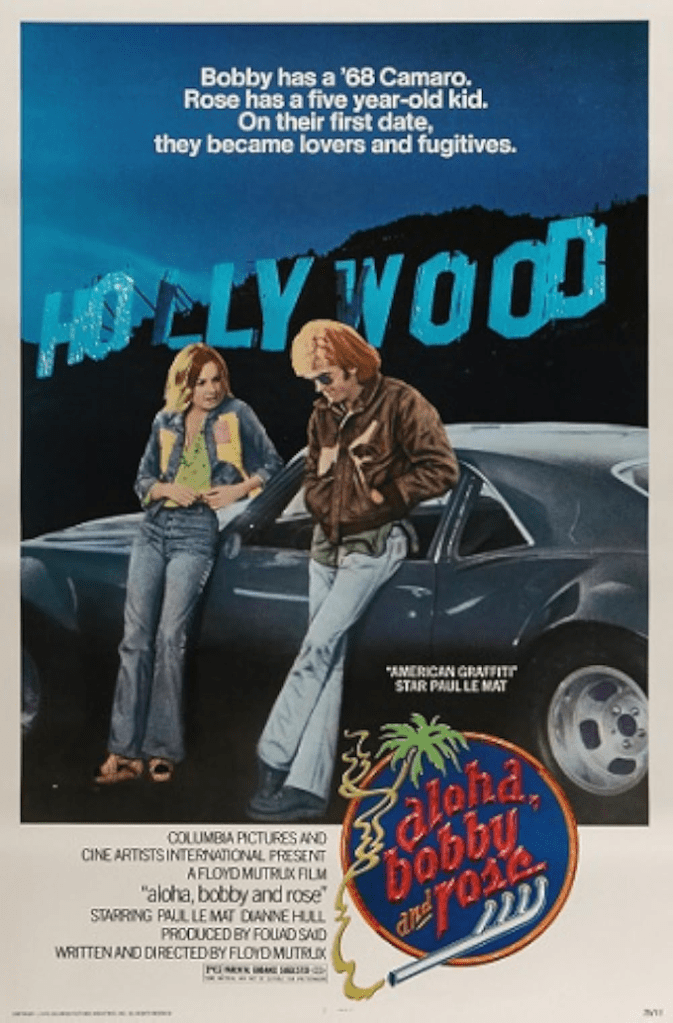

By the time Aloha Bobby and Rose debuted in 1975, we had already seen hot rods, star-crossed lovers misunderstood by society, and any combination of the two. But if American Graffiti and Bonnie & Clyde (in its own way) were nostalgia trips and a look at how far we’ve come, then Floyd Mutrux’s film is a mark of the times in nearly every way imaginable. But I’m not so sure it does much else.

On the very surface, at least, we get to see a snapshot of Los Angeles in the mid-‘50s, with billboards and marquees highlighting famous figures from the era. Aloha Bobby and Rose is billed as a road trip movie but I was much more into it when the leads were just driving around their home town.

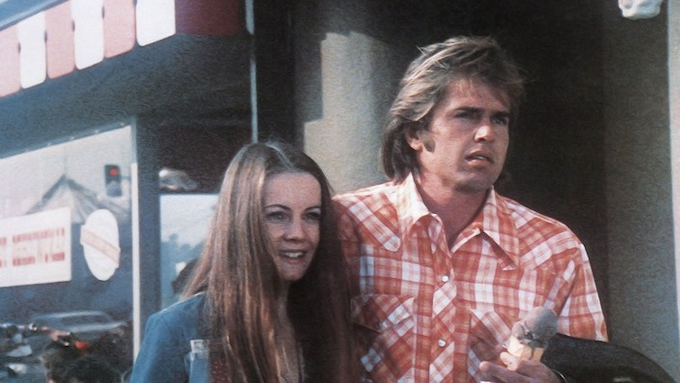

As much potential that’s bubbling under the surface, the real issues with the film are a lack of structural organization and narrative flow. Loose ends never amount to anything, characters of seeming importance disappear without any closure, and the huge decisions made by our protagonists feel manufactured by a screenwriter (Mutrux) almost every step of the way. The two titular characters (Paul Le Mat, who’s also in American Graffiti, and Dianne Hull) simply do — they hardly think or feel, because it’s easier to justify their actions that way. And even when they seem to think or feel even a little bit, it’s never convincing enough.

Absent is the confusion of the young couple in Badlands or the disillusion of The Conversation. We just see two young adults complacent with what life has handed them and halfheartedly dreaming of something more. They know their hypothetical trip to Hawaii is never coming but they have fun playing pretend.

Still, Aloha Bobby and Rose has enough undercooked ideas to pull from. There’s a reference to Rose as a contestant on Let’s Make a Deal, where she’s given a trip to Hawaii but opts to see what’s behind Door #2 instead, only to reveal a tricycle (“Something you can use to ride around Hawaii”). The Doors obvious symbolize opportunity, gut decisions, and, as it were, destiny. Sometimes in life, if not usually, you get Doors #1 and #2 at the same time and just have to figure out what to do with your prize after the fact. But then again, sometimes it’s easier for everything to just go back to normal again.

Leave a comment