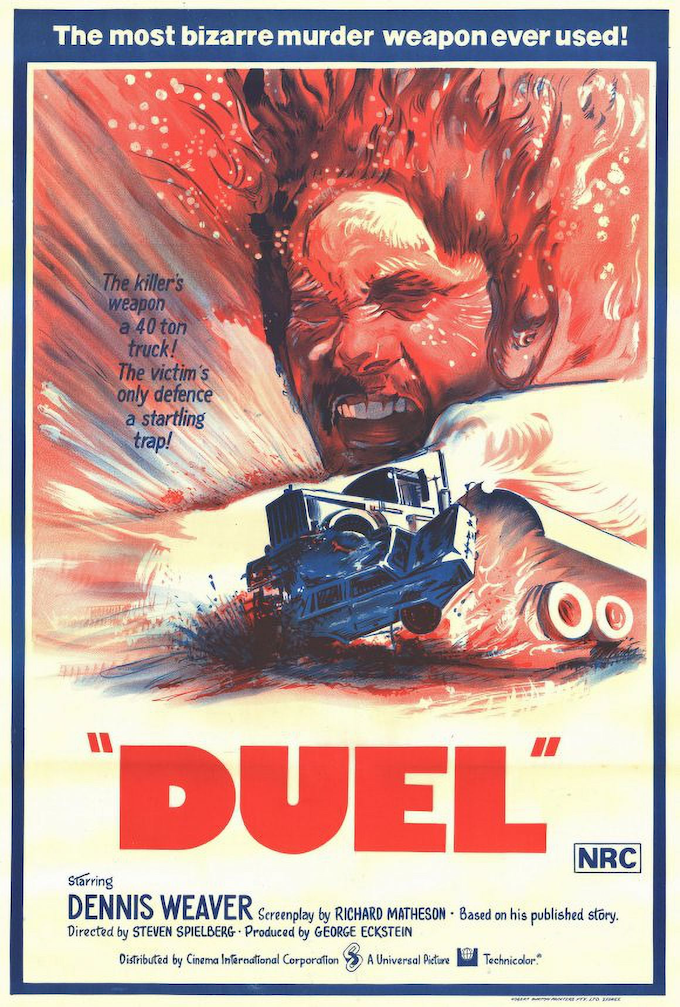

If you’ve ever had someone riding your tail on a winding, treacherous road while you’re barely going the speed limit, you may just get a taste of what the protagonist feels like in Steven Spielberg’s harrowing debut feature Duel.

There’s not much plot or dialogue — especially if you can get your hands on the original 71-minute television movie — but Spielberg puts it all on display, building tension through cuts, angles, and panning. Most of us would call this filmmaking!

David Mann (Dennis Weaver), a traveling salesman, spends his days venturing up and down a two-lane highway in the Mojave Desert. Until one day, he decides to legally pass a tanker truck in the left lane. But for reasons that are wisely never explained, this trucker spends the remainder of the movie harassing David, even to the point of nearly killing him a few times.

In what amounts to basically a 71-minute scene, Duel turns into a character study of a man who we know nothing about. We see his vulnerabilities, his resolve. He becomes the surrogate for the audience, vicariously inviting us to wield our own submissiveness due to our terror of the trucker. The most realistic fears might just be the inexplicable. They haunt you the longest as we search for answers.

But we learn a lot about the trucker as well — as much mental anguish as we can possibly glean from a faceless person. There’s a moment of sadness towards the end of the 2nd act where David finally gets out of his car to confront the trucker parked on the side of the highway. However, as David approaches the vehicle, the trucker edges further down the road, almost hinting that he might actually be afraid of confrontation himself. He might not be so tough after all — at least not without the safety net of his truck. In the process of trying to show his machismo, he inadvertently proves David to be the more courageous individual.

Every second of this brief movie is filled with something that progresses the simple plot, with Spielberg heightening the granular elements of the story in order to create something of a gestalt whole.

You can feel the speed of the cars through Spielberg’s editing and, if you can use this term with vehicular characters, blocking. The film score of swirling strings dips in and out for emphasis, but this just complements the diegetic music of humming combustion pistons and revved engines.

In 1971, most films would’ve ended with something dark. The truck driver continuing his rampage, the protagonist coming up short, the two of them going out in flames together. However, this is where Spielberg began. He yearned for the happy ending, the exultant. It may have felt out of place during this decade but would serve him well in future eras where it was acceptable to romanticize victory.

Duel, with all its grit and rough edges, is a tour de force nonetheless — one of many during the most prolific career of any filmmaker ever.

Leave a comment