A year before Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the characters in Chuck Vincent’s prototypical vansploitation flick weren’t yet troubled by the idea of potentially picking up a psycho cannibal hitchhiker when aimlessly heading out on a sticky summer drive. The only people our protagonists come across are kleptomaniacs, pseudo-cult leaders, and ostensibly religious con men. In 1973, America was changing. Distrust, disillusion, and blitheness were all plaguing our youth while creating a virulent generation gap between us and our parents. The hippie movement had proven to be idealistic at best and millions of teenagers were learning the hard way that they still needed to eventually become adults.

We can’t all be aimless motorcyclists with nowhere to be and no time to get there. Many of us are destined to be angry grownups barking orders at people in our household as we try to read the newspaper. “It’s not healthy to start the day without breakfast…you’ll grow up to be an idiot!”

You can attempt to relive your youth all you want but the one thing that you can never truly experience again once you’ve grown up is the joy and simplicity of summer vacation. The two main characters in this oft-forgotten-about road flick are anticipating college and the real world, but not before they fill their one final summer with unbridled escapades. While it doesn’t dawn on them until the very end that this had truly been their last hurrah, the lack of responsibility had been informing their debauchery from the start.

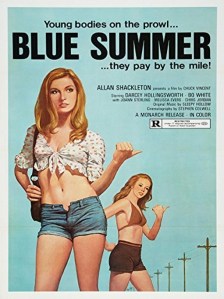

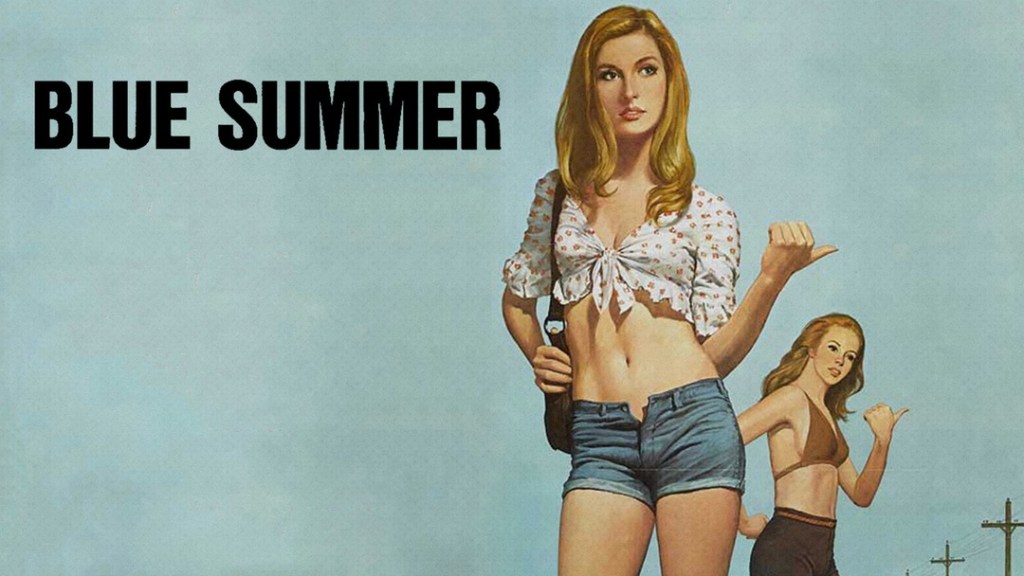

Blue Summer follows two recent high school grads Tracy and Gene (Davey Jones and Bo White) as they embark on an aimless adventure driving the countryside in their van as they await the end of summer. Along the way, they meet a host of mostly strange individuals, including a silent and intimidating biker (Jeff Allen) who doubles as their guardian angel. Treating the open road as a metaphor for an undecided future, the movie attempts to focus on the freedoms afforded by our youth, albeit with a strong emphasis on sexual proclivities that most late teens won’t quite relate to anyway. Writer-director Chuck Vincent was 33 years old at the time and would eventually become known for a plethora of pornographic films throughout his career.

The abundance of elongated sex scenes aside, Blue Summer is bookended by the wistful acquiescence of aging into adulthood. The stuff in the middle winds up serving as mere context for the film’s more reflective themes, especially as it relates to summertime. It’s a perspective that the characters within the film can’t possibly fathom the weight of yet and that the older audience members can relate to all too well as we reflect on our own summers gone by. Most of us may wish that we had been more present during that time in our lives — even if we don’t ever envy the experiences shared by Tracy and Gene.

American Graffiti was tackling a similar poignancy just a few months prior (though getting there in a much more unique way) and would, of course, come to change the very nature of teen movies from here on out. I’m curious how much of the denouement was influenced by George Lucas’ seminal picture.

Blue Summer doesn’t need to be remembered, especially if you don’t want to sit through 60+ minutes of softcore pornography just to get to its more relatable themes. It also won’t scratch any nostalgic itch of later summer flicks such as Meatballs and Little Darlings. As a cultural curiosity, Vincent’s strange odyssey helped inspire the vansploitation sub-genre of the late ‘70s, which, too, is nearly as forgotten about as this movie.

Leave a comment