Street Trash may be the most schlocky, irreverently grotesque gore fest of the 1980s. However, there’s some real sadness present under the surface. Unlike a lot of its horror contemporaries, there is a real connection between the gore and the plot, and there are actual themes at play.

The movie revolves around a local homeless population and an expired case of cheap booze that, upon consuming it, quickly turns their bodies to neon-colored mush. However, the alcohol is not used by any one person as a deliberate weapon. In fact, the liquor store owner selling the bottles ends up becoming one of the victims himself. There’s no evil mastermind, no government agency trying to commit mass genocide (like in the similar film, The Stuff). The liquor does not discriminate (like the shark in Jaws), yet it’s not even really an act of nature either. And so, we’re left to observe that it’s really the homeless people who are killing themselves with their own vices. Or is it society’s view of the homeless that contributes to their inability to get out of this hole?

The film draws some looser parallels to napalm used during the Vietnam War. For those burned or killed by the jellied gas, the source of the poison did not matter. Once you begin to melt, you’re not analyzing the culprit.

Street Trash hardly follows a protagonist. Instead, we learn about the different characters within this local encampment living in a junkyard. Amongst the community, there are good guys, bad guys, and those operating in between the two. There’s also a de facto villain named Bronson (Vic Noto), who bullies, lusts, and kills. He’s almost as deadly as the liquor, but even he is seen as a product of his past. He’s the antagonist for the same exact reason why he’s homeless to begin with. He’s a Vietnam vet who suffers from extreme mental illness. And the film is wise enough to allow us to sympathize with him a bit as well.

I found it impressive how objective the movie’s approach was in its commentary on homelessness. It shows that the discussion isn’t as black-and-white as people have made it seem like from both sides. It helps that the camera work is very deliberate. Director J. Michael Muro would go on to be a camera operator on James Cameron’s biggest projects, as well as the DP for 2004’s Crash. He could have easily leaned his cinematography here towards the schlocky pretense but instead uses it as a crucial aspect of telling his story.

I see inspiration from Street Trash in the recent works by techno-core junky Michael Bilandic and even the ostensible crudity of the Safdie brothers — both have a history with cinematographer Sean Price Williams, who’s undoubtedly watched the 1987 movie a few times in his life.

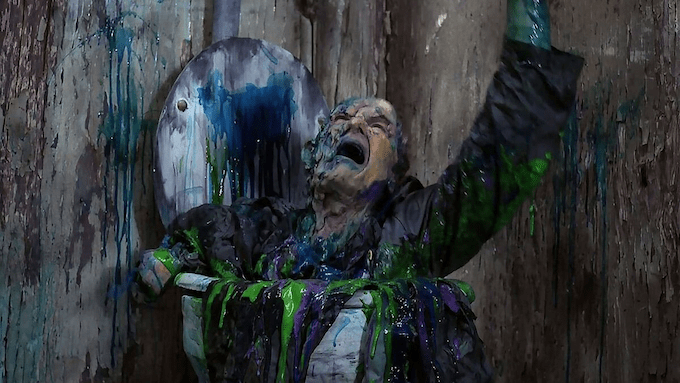

Dark, twisted, and perhaps the mere definition of ‘80s schlock, Street Trash has some of the best and grossest gore of the era, while still showcasing a near beauty in the color design of its neon-swirled slime. Adding a layer to the death sequences beyond what we had already seen by that point, the film makes it so that there’s a literal appeal to the body-melting, allowing the audience different options for how it responds to the film.

Leave a comment